Locus Ludi: The Cultural Fabric of Play and Games in Classical Antiquity

The research project Locus ludi has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 741520): ERC Advanced Grant 2017-2022/2023

The ERC operates according to a “curiosity-driven”, or “bottom-up”, approach, allowing researchers to explore new opportunities in any field of research. Accordingly the portfolio of ERC funded projects covers a wide range of topics and research questions.

Locus Ludi goes on. Join the the Cost Action GameTable #442215 !

New outcomes : Reckoning means playing…

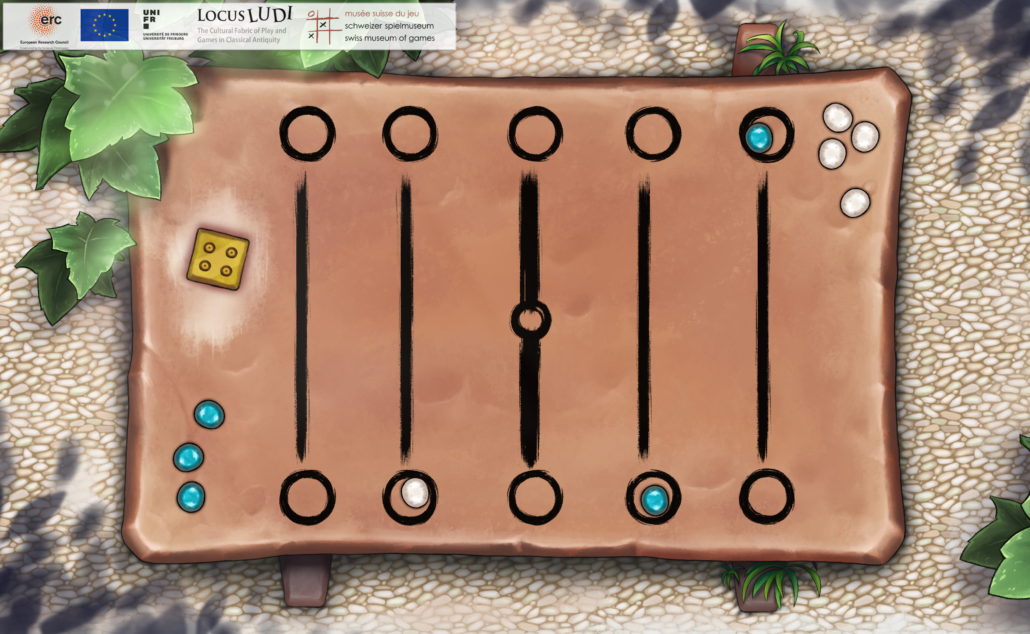

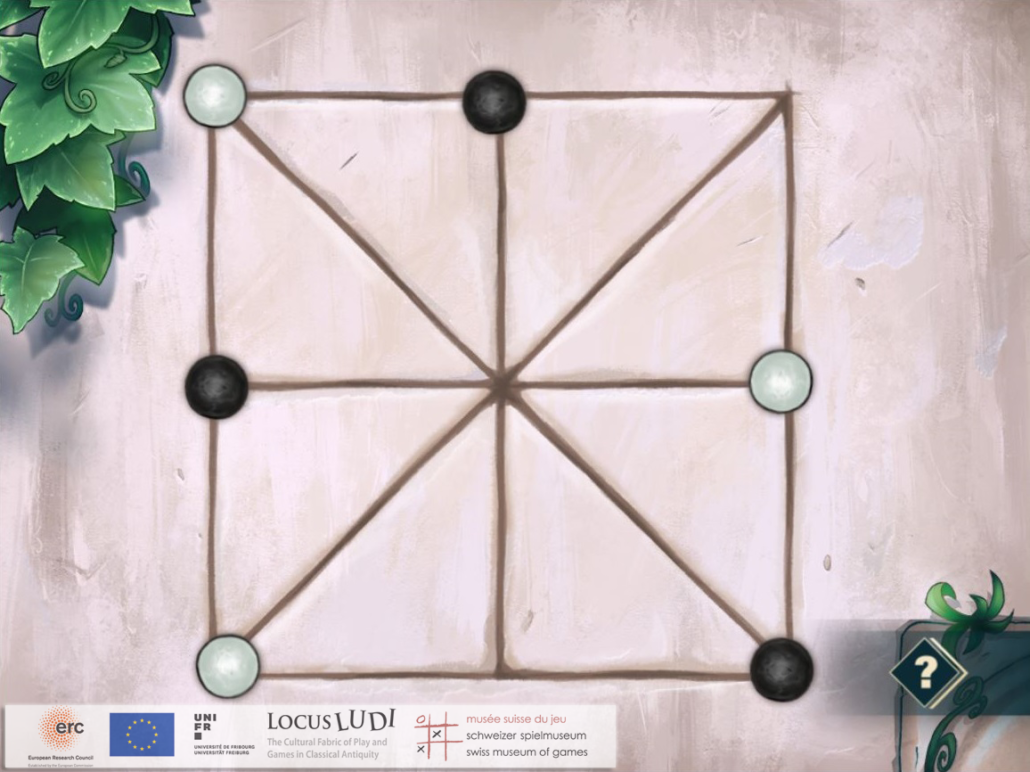

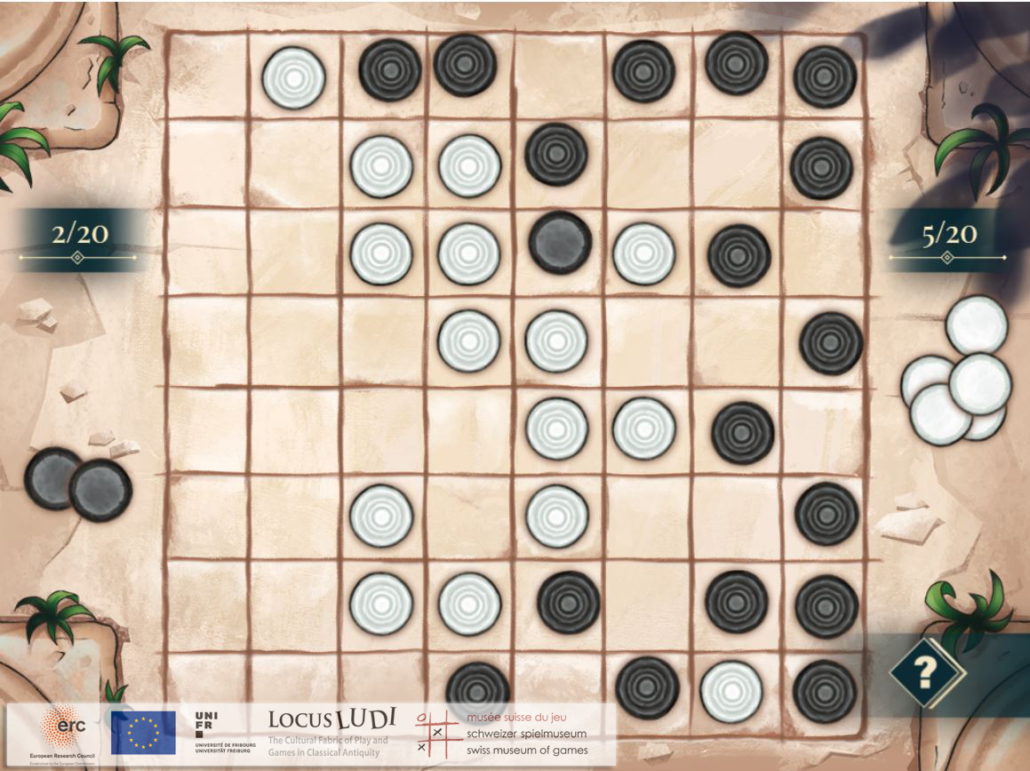

Test the Greek abacus and Pente Grammai, and visit the exhibition “From Board to keyboard. Archaeology of video game “, Swiss Museum of Games, La Tour-de-Peilz . With the support of SNF Agora Grant 2024.

Recent outcomes: online games

Recent outcomes: Monographs and special issues in peer-reviewed journals

Forthcoming

Attia, A., Le jeu du kottabos. Guide illustré, Collection Jeu/Play/Spiel, Liège, in preparation

Dasen, V., Louis Becq de Fouquières (1869), Les jeux des anciens, commented and augmented reedition, Collection Jeu/Play/Spiel, Liège, Presses Universitaires de Liège, in press.

Dasen, V., Kanibal. Dochodzenie w sprawie antycznej rzeêby (polish transl. Julia Wollner), Warsaw, in press, 2025.

Dasen, V., L’enigma del Cannibale. Inchiesta su una scultura antica (it. transl. Fabio Spadini), Milano, in press.

Carè, B., Astragaloi. A “Toy” Story, Collection Locus Ludi, Darmstadt, WBG/Mainz, Ph. von Zabern, in preparation.

Schädler, U., Ephesische Spiele, Collection Locus Ludi, Herder Verlag, in press

Ruchynska O., Play and Games in the Northern Black Sea Poleis: public and private aspects, Darmstadt, WBG/Mainz, Ph. von Zabern, in preparation.

Vespa, M., Le jeu dans l’Antiquité grecque et romaine. Une anthologie commentée, Coll. Jeu/Play/Spiel, Liège, Presses Universitaires de Liège, in press.

Bianchi, Ch., Pupae. Bambole articolate di età romana, Association des publications chauvinoises, Mémoires, LX, Chauvigny, 2025. Order the book/Open access

Bianchi, Ch., Pupae. Bambole articolate di età romana, Association des publications chauvinoises, Mémoires, LX, Chauvigny, 2025. Order the book/Open access

Attia, A. et Dasen, V. (éds.), Louis Becq de Fouquières, Les jeux des Anciens et leur réception à l’époque moderne (XVIe – XIXe siècles), Collection Jeu/Play/Spiel, Liège, 12, Presses Universitaires de Liège, 2025. Order the book

Attia, A. et Dasen, V. (éds.), Louis Becq de Fouquières, Les jeux des Anciens et leur réception à l’époque moderne (XVIe – XIXe siècles), Collection Jeu/Play/Spiel, Liège, 12, Presses Universitaires de Liège, 2025. Order the book

Pace, A., Penn, T., Schädler, U. (eds), Games in the Ancient World: Places, Spaces, Accessories, Dremil-Lafage, Mergoil, Monographies Instrumentum 79, 2024. Order the book/Open access

Pace, A., Penn, T., Schädler, U. (eds), Games in the Ancient World: Places, Spaces, Accessories, Dremil-Lafage, Mergoil, Monographies Instrumentum 79, 2024. Order the book/Open access

Dasen, V., Dossier : Antike Puppen. Zwischen Spiel und Ritual, Antike Welt, 2/2024. Order the book.

Dasen, V., Dossier : Antike Puppen. Zwischen Spiel und Ritual, Antike Welt, 2/2024. Order the book.

Véronique Dasen, Le jeu comme métaphore. Images ludiques de Grèce ancienne / Play as Metaphor. Ludic Images from Ancient Greece, coll. Jeu/Play/Spiel, Liège, Presses Universitaires de Liège, 2024. Order the book (FR). Order the book (EN). Open access (FR)

Véronique Dasen, Le jeu comme métaphore. Images ludiques de Grèce ancienne / Play as Metaphor. Ludic Images from Ancient Greece, coll. Jeu/Play/Spiel, Liège, Presses Universitaires de Liège, 2024. Order the book (FR). Order the book (EN). Open access (FR) Véronique Dasen et Typhaine Haziza (dir.), Violence et jeu, de l’Antiquité à nos jours, Caen, Presses universitaires de Caen, 2023. Bibliographie |Order the book. Open access

Véronique Dasen et Typhaine Haziza (dir.), Violence et jeu, de l’Antiquité à nos jours, Caen, Presses universitaires de Caen, 2023. Bibliographie |Order the book. Open access

Alessandro Pace, Ludite Pompeiani. Nuove prospettive sulla cultura ludica dell’antica città, Firenze, All’Insegna del Giglio, 2023. Order the book.

Alessandro Pace, Ludite Pompeiani. Nuove prospettive sulla cultura ludica dell’antica città, Firenze, All’Insegna del Giglio, 2023. Order the book.

M.-L. Arnette, V. Dasen (eds), Joueuses !, Clio. Femmes, genre, histoire 56, 2022. Open access

M.-L. Arnette, V. Dasen (eds), Joueuses !, Clio. Femmes, genre, histoire 56, 2022. Open access

V. Dasen, V. Pirenne-Delforge (eds), Dossier Des Dieux, des jeux, du hasard ?

V. Dasen, V. Pirenne-Delforge (eds), Dossier Des Dieux, des jeux, du hasard ?

Part I, Kernos 35, 2022. Open access

Part II, Kernos 37, 20224. Open access

V. Dasen, M. Vespa (eds), Toys as Cultural Artefacts in Ancient Greece, Etruria, and Rome, Dremil-Lafage (Instrumentum 75), 2022. Order book. Open access (pdf link at the bottom of the page)

V. Dasen, M. Vespa (eds), Toys as Cultural Artefacts in Ancient Greece, Etruria, and Rome, Dremil-Lafage (Instrumentum 75), 2022. Order book. Open access (pdf link at the bottom of the page)

V. Dasen, Le Cannibale / Enquête sur une sculpture antique, Paris, Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA)

V. Dasen, Le Cannibale / Enquête sur une sculpture antique, Paris, Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA)

Collection Dits, 2022, ISBN 978-2-917902-44-8

Véronique Dasen, Thomas Daniaux (éd.), “Dossier: Locus Ludi : quoi de neuf sur la culture ludique antique ?”, Pallas, 119, 2022 | Open Access

Véronique Dasen, Thomas Daniaux (éd.), “Dossier: Locus Ludi : quoi de neuf sur la culture ludique antique ?”, Pallas, 119, 2022 | Open Access

R. Graells i Fabregat, A. Pace, M. Pérez Blasco (eds), Warriors@Play, Proceedings of the International Congress held at the Museum of History and Archaeology of Elche, 28th May 2021, Alicante, University of Alicante, 2022. Open Access

R. Graells i Fabregat, A. Pace, M. Pérez Blasco (eds), Warriors@Play, Proceedings of the International Congress held at the Museum of History and Archaeology of Elche, 28th May 2021, Alicante, University of Alicante, 2022. Open Access

Barbara Carè, Véronique Dasen, Ulrich Schädler (eds), Back to the Game: Reframing Play and Games in Context. XXI Board Game Studies Annual Colloquium, International Society for Board Game Studies, April, 24-26, 2018, Benaki Museum – Italian School of Archaeology at Athens (Board Games Studies Supplement), Lisbon, Associação Ludus, 2021. Order the book. Open access

Barbara Carè, Véronique Dasen, Ulrich Schädler (eds), Back to the Game: Reframing Play and Games in Context. XXI Board Game Studies Annual Colloquium, International Society for Board Game Studies, April, 24-26, 2018, Benaki Museum – Italian School of Archaeology at Athens (Board Games Studies Supplement), Lisbon, Associação Ludus, 2021. Order the book. Open access

Véronique Dasen, Typhaine Haziza (dir.), Dossier Jeu, normes et transgressions, Kentron, 36, 2021. Open access

Véronique Dasen, Typhaine Haziza (dir.), Dossier Jeu, normes et transgressions, Kentron, 36, 2021. Open access

Véronique Dasen (dir.), Dossier Eros en jeu, Mètis. Anthropologie des mondes grecs anciens, N.S. 19, 2021 | Table of contents | Open Access

Véronique Dasen, Marco Vespa (dir.), Play and Games in Classical Antiquity: Definition, Transmission, Reception, Liège, Presses Universitaires, coll. Jeu/Spiel/Play 2, 2021, 518 p. Open Access | Table of contents | Introduction: In search of a definition | Order the book

David Bouvier, Véronique Dasen (dir.), Héraclite, le temps est un enfant qui joue, Liège, Presses Universitaires, coll. Jeu/Spiel/Play 1, 2020, 338 p. | Order the book | Table of Contents | Open Access

David Bouvier, Véronique Dasen (dir.), Héraclite, le temps est un enfant qui joue, Liège, Presses Universitaires, coll. Jeu/Spiel/Play 1, 2020, 338 p. | Order the book | Table of Contents | Open Access

Reviews: Kernos 34, 2021

Véronique Dasen, Marco Vespa (dir.), “Dossier: Bons ou mauvais jeux? Pratiques ludiques et sociabilité”, Pallas, 114, 2020 | Order the issue– table of contents | Introduction |Open Access

Dossier “Locus Ludi: Les dés atypiques”, Instrumentum: bulletin du Groupe de travail européen sur l’artisanat et les productions manufacturées dans l’Antiquité 52, december 2020, p. 26-46 (dir. V. Dasen, with E. Alevizou, Th. Daniaux, E. Lovergne, A. Pace). Open Access

Dossier “Locus Ludi: Les dés atypiques”, Instrumentum: bulletin du Groupe de travail européen sur l’artisanat et les productions manufacturées dans l’Antiquité 52, december 2020, p. 26-46 (dir. V. Dasen, with E. Alevizou, Th. Daniaux, E. Lovergne, A. Pace). Open Access

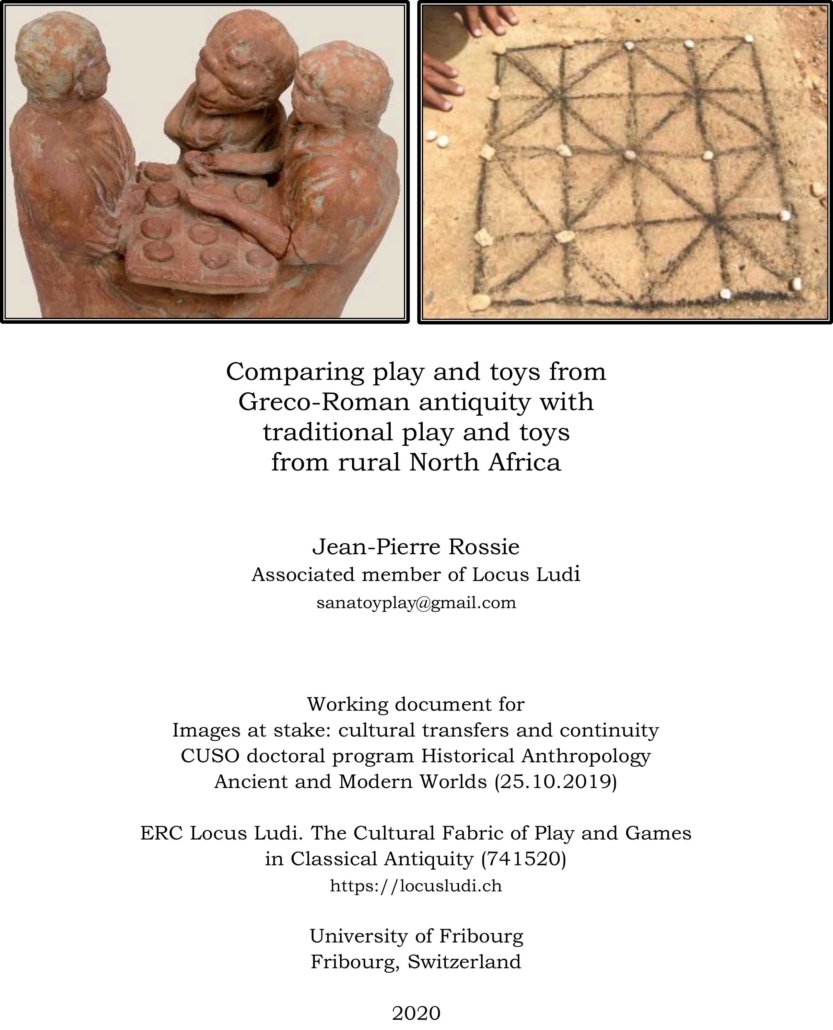

Jean-Pierre Rossie, Comparer des jeux et jouets de l’antiquité gréco-romaine avec des jeux et jouets traditionnels du monde rural nord-africain / Comparing Greco-Roman and North African Play and Toys, Fribourg, 2020 | OpenAccess: French / English

Jean-Pierre Rossie, Comparer des jeux et jouets de l’antiquité gréco-romaine avec des jeux et jouets traditionnels du monde rural nord-africain / Comparing Greco-Roman and North African Play and Toys, Fribourg, 2020 | OpenAccess: French / English

Jean-Pierre Rossie, Vegetal Material in Moroccan Children’s Toy and Play Culture. Printed in Dasen V., Vespa M., (eds), Toys as Cultural Artefacts in Ancient Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Cultures. Anthropological and Material Approaches (in press). Open access English

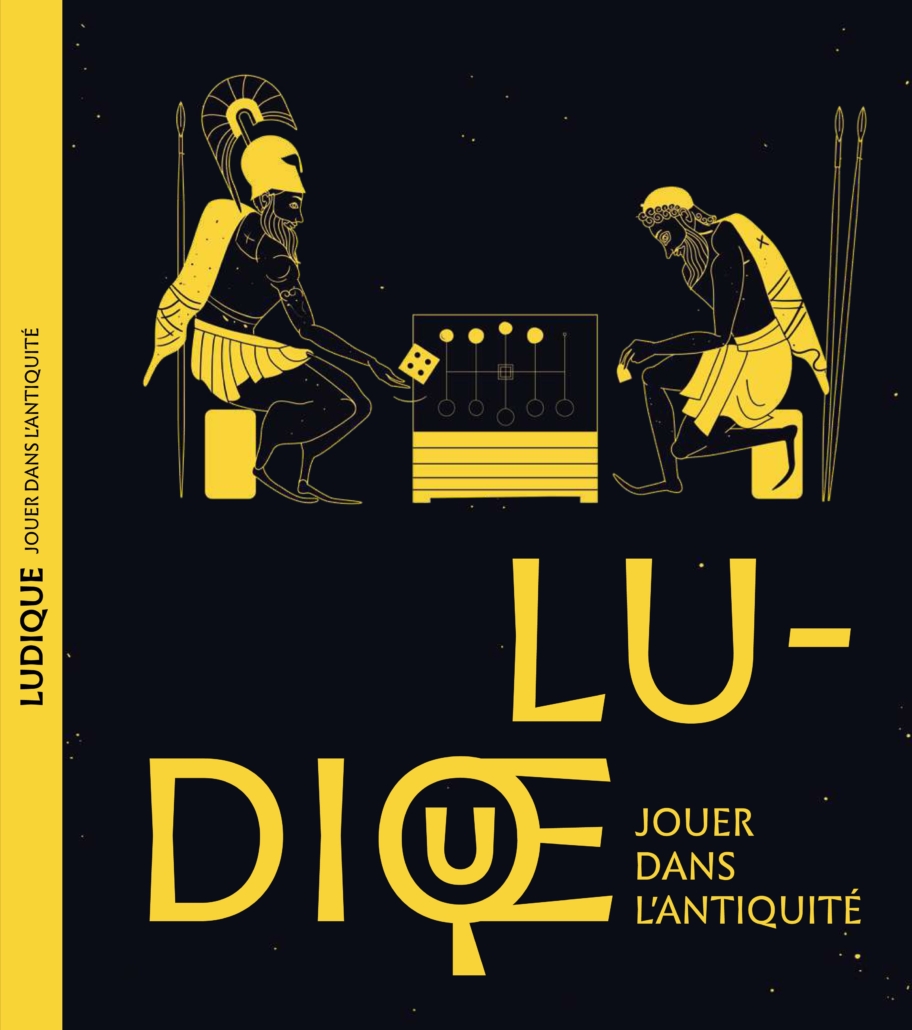

Véronique Dasen (dir.), Ludique. Catalogue de l’exposition ‘Ludique! Jouer dans l’Antiquité’, Lugdunum-musée et théâtres romains, 20 juin-1er décembre 2019, Gent, Snoeck, 2019 Open Access.

Véronique Dasen (dir.), Ludique. Catalogue de l’exposition ‘Ludique! Jouer dans l’Antiquité’, Lugdunum-musée et théâtres romains, 20 juin-1er décembre 2019, Gent, Snoeck, 2019 Open Access.

![]() Salvatore Costanza, Giulo Polluce, Onomasticon: excerpta de ludis. Materiali per la storia del gioco nel mondo greco-romano, Alessandria, Edizioni dell’Orso, 2019 | OpenAccess

Salvatore Costanza, Giulo Polluce, Onomasticon: excerpta de ludis. Materiali per la storia del gioco nel mondo greco-romano, Alessandria, Edizioni dell’Orso, 2019 | OpenAccess

Véronique Dasen, Ulrich Schädler (dir.), “Dossier: Jouer dans l’Antiquité. Identité et multiculturalité”, Archimède. Archéologie et histoire ancienne, 6, 2019, 71-212 | OpenAccess

Véronique Dasen (dir.), “Dossier: Jeux et jouets dans l’Antiquité. À la redécouverte de la culture ludique antique”, Archéologia, 571, December 2018 – H. Ammar, M. Chidiroglou, V. Dasen, M. Fuchs, E. Karakitsou | OpenAccess

Véronique Dasen (dir.), “Dossier: Jeux et jouets dans l’Antiquité. À la redécouverte de la culture ludique antique”, Archéologia, 571, December 2018 – H. Ammar, M. Chidiroglou, V. Dasen, M. Fuchs, E. Karakitsou | OpenAccess Véronique Dasen, Typhaine Haziza (dir.), “Dossier: Jeux et jouets”, Kentron. Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde antique, 34, 2018, 17-128 | OpenAccess

Véronique Dasen, Typhaine Haziza (dir.), “Dossier: Jeux et jouets”, Kentron. Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde antique, 34, 2018, 17-128 | OpenAccessOur full list of publications (team and associated researchers) (with Open Access links)

Project summary

Ludic culture evolves over time and this project intends to provide a benchmark by reconstructing this history in the Greek world, from the birth of the city-state, c. 800 BCE, to the Roman conquest in 146 BCE, and in the Roman world from the Republican age, c. 500 BCE, to the end of the Western Roman Empire, c. 500 CE. Locus Ludi will identify, categorize and reconstruct ancient games thanks to close linguistic, historical, archaeological, typological, topographical, iconographic, and anthropological studies. Ludic culture also mirrors interactions between different populations, as in the Romanisation process, and religious shifts. The research will be informed by theoretical studies of the past as well as by gender and education studies. It will generate a new vision of the cultural fabric of ancient society, provide models for training and research in related fields, as well as up-to-date material for schools, museums, and libraries. Understanding the educational, societal and integrative role of play in the past is important to understand the present and widen the debate on high tech toys and new forms of sociability.

Play and games were ubiquitous in antiquity, among free men and slaves, men and women, adults and children, in town and country. Even gods played. Ludic culture created communities from early childhood to a ripe old age. Did these groups play together, or did they play different games, with distinct rules? And did they play similar games to us? This interdisciplinary project will provide the first comprehensive study of the evidence. Written, archaeological and iconographic sources are abundant, but forgotten in museums and libraries. This neglect is due to the modern Western view of games as children’s pastime, if not a waste of time. Ancient play and games reflect the gendered, religious, economic, and political fabric of a society, as much as they shape the lives of players by transmitting a cultural identity and an intangible heritage.

Three research priorities

The project is based on a pluridisciplinary and comparative approach of ancient sources (written, archaeological, iconographic). The research explores three aspects: 1) education and lost rules, 2) identity, sociability and ideology, 3) childhood and gender.

1. Written sources

First focus: Reconstructing a lost heritage: There is no consensus as of yet on how to translate the vocabulary relating to play and gaming equipment. The aim here is to make a Greek and Latin lexicon of play and games in literary, epigraphic, and papyrological sources, associated with new translations of collected texts that will form an Anthology. This will provide far-reaching outcome, clearing a number of misconceptions (such as astragaloi commonly translated as ‘dice’).

Second focus: Pollux and children’s games: The Onomasticon written by the lexicographer Pollux of Naucratis (2nd cent. CE), contains the description of many children’s games. It is regularly cited, using the edition by Bethe 1931, but it has never been studied in depth. A new scientific edition, with translation and commentary represents a long-awaited milestone. This task involves reflecting on the reception of ancient games. This research will be facilitated by collaborations with anthropologists working on oral and children memories, as well as with specialists in sciences of education and cognitive psychology.

Third focus: Play, games, and education situates Pollux in a wider cultural context.A research will be conducted on Greek and Roman cognitive, psychological, emotional aspects of games that are more diverse and nuanced than usually claimed. In the Satyricon 4.1, Asciltos’ complain that children play at school (nunc pueri in scholis ludunt!) is thus translated in 1913 as “As it is, the boy wastes his time in school” (Loeb).

2. Archaeological sources: Locus ludi

We concentrate on representative sites and find contexts, using GIS software to record the spatial distribution of game devices according to chronology, typology, context. The material is rare, partly because it is not yet identified or overlooked, or the identification is debated. On selected sites, games pieces (knucklebones, dice, counters…) and game boards will be catalogued and classified in order to create a reference typology, paying attention to mistaken identifications. The identity of the players and the function of the games will be analysed according to context, domestic, public, sacred, funerary, in the search also of multicultural interactions.

First focus: Roman towns, east and west.

The aim is to analyse games as mirrors of the social dynamics of urban culture in public and private spaces, among common folk and élite, comparing Asia Minor towns, Vesuvian cities, Ostia Antica, Rome, provincial towns, and Roman legionary camps. What did an Egyptian trader play in Pompeii or Ostia, or a Spanish legionary on the Roman limes? What did they play together and did it change over time? Some games were played uninterruptedly, by Christians too.

Second focus: Games in liminal places

Since the Greek Geometric period, game boards and pieces are also found in liminal contexts, like tombs. In sanctuaries, game boards, dice, and knucklebones embody the negotiating process characterizing Graeco-Roman religion. The task will focus on the symbolic, religious or identity function of games in funerary and religious contexts.

3. Iconographic sources

First focus: Children as social actors

The concept of ‘family games’ emerged in the eighteenth century with a new type of Bourgeois family, but the common statement that adults, especially fathers, rarely played with children in antiquity can be challenged, as does the notion of children as passive consumers. Work will be based on the corpus of Attic miniature vases, the so-called Anthestheria choes (c. 430-380 BCE) available in the Fribourg database Callisto, and in larger resources, such as the Beazley Archive at Oxford. The analysis of the visual discourse will provide new insights in children’s agency. It will investigate children at play with siblings, friends, children, and adults (child minders, free or not, parents or grandparents), according to age group, gender, and social status, and the types of play, free or adult-managed, compared with other media.

Second focus: Games and the fabric of gender

Ancient texts and iconography reveal that like music and musical instruments, games too were categorized as male or female. As today gendered games contributed to the fabric of women and men by make-believe play and ‘role-learning’. Pollux often specifies who plays the game, such as Pentelitha (five stones), reserved to unmarried girls. The criteria change over time. Psellos (11th cent. CE) tells the story of a boy who only liked girls’ games and gives a gendered list including nuts and whipping tops for boys. The task will focus on the ludic interaction of women and men, comparing Greek and Roman iconography, realities and representations. On Attic and South Italian vases (5th-4th cent. BCE), unmarried young men and women thus interact by playing skill and chance games that deliver love oracles reflecting Greek social expectations.